For more than a decade, I have been watching, listening and photographing the collapse of the family farm in my county, one of the most iconic and important institutions in American history and American life.

The abandonment of these farms by government and people who eat is yet another testament to the devastation wrought by the corporate idea, and its de-humanizing rape and destruction of so much of rural America, the very birthplace of the American experience.

All over the country, people are fleeing rural life, as they have for decades, farms are sold to developers, purchased by hobby farmers, or left abandoned for years.Family farmers are vanishing in every part of the country.

After World War II, the returning soldiers fled the hard life of the farm for the cities, and the government decided the family farmer was too small and inefficient for the modern world. There was a great migration from the heartland to the cities and coasts, children left their farmer parents for a different life, and the agribusiness – bigger and bigger – ravaged the small farmer, ruined Main streets all over America, was a horror for farm animals and devastated the land.

This was the origin of much of the bitter divisions we see in our political life today – the rural people who were left behind and suffered for so long, the urban people with money, jobs and hopeful futures. It was a ripe formula for a demagogue.

No individual can really compete with a giant corporation, they are identity and soul killers, the farmers have known this for years, but never quite understood the political implications of who they voted for. They have a self-acknowledged to act in their worst self-interest, and live at the mercy of feckless politicians and regulators, all of whom seem to care nothing about them.

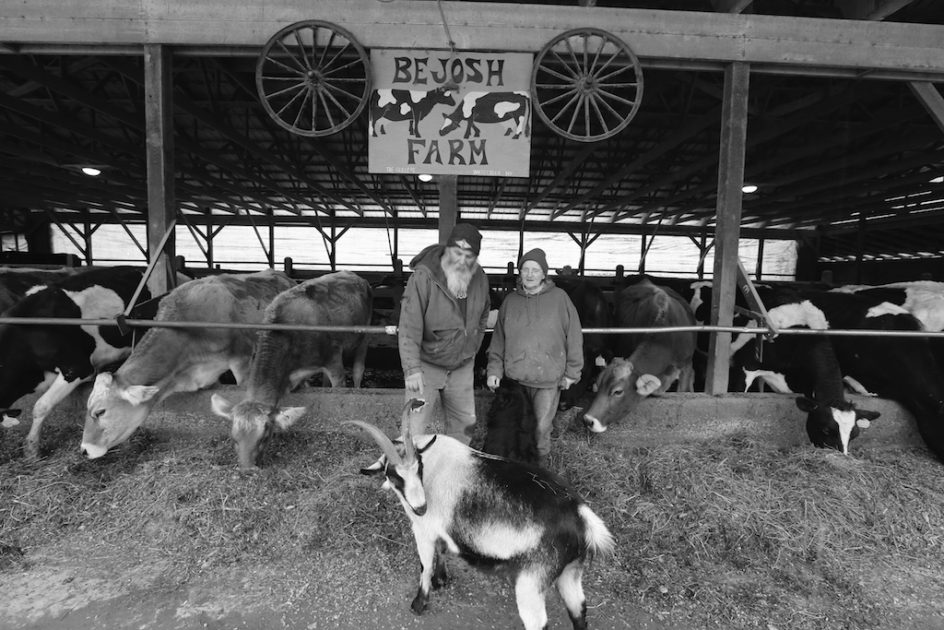

If you wish to understand the increasingly difficult and sometimes hopeless life of the farm, I can recommend two remarable sources of information and truth. One is the funny, honest and sometimes wrenching Bejosh Farm Journal blog, a/k/a My Farmer And Me, written and produced daily by my friends Ed and Carol Gulley, long-time dairy farmers whose milk prices are the same as they were in 1970 while their costs for feed and equipment skyrocket every year.

There is so much truth and honesty in their writing and photographs.

I am in awe of their hard and relentless work, long hours and perpetual exhaustion. They love their life, and have worked faithfully on their, but their continuous struggle only gets harder. And they are fighting for their very existence.

We are proud to know and call them friends, but they remind me that farming is not a business, but a culture and way of life, the best hope for many animals and the land and for the future of good food and healthy land. Ed and Carol are working on a book about the seasons on their farm, they are having an Open House on Bejosh Farm in June.

Ed has become a successful artist as well, his farm art has sold over the country. You can read about it on their blog. We think of them often, Ed says he and I are “brothers from different mothers,” a high compliment to me.

The second and very powerful and prescient writing about farm life was written by the farmer, author, poet and environmentalist Wendell Berry and published in 1977, it is called “The Unsettling Of America: Culture And Agriculture,” and it is profoundly important book.

It is perhaps even more relevant in our society today than it was when written.

It opened my eyes to the struggle of the family farmer and their abandonment by politicians, economics, agri-corporations and those of us who shop at a supermarket crammed to the rafters with cheap and plentiful food without having a clue as to where it comes from or how it was grown or what it took to get it there.

With the death of the family farm, we all lose so much more than we ever grasped.

The farmer is a metaphor for the proud and free and individual life that America made possible, and their story has become our story, their fate our fate. We are just beginning to wake up to that.

More than nine billion animals life often horrific lives on corporate industrial farms, the animal rights movement loves to harass and persecute on farmers but seems to never get around to the true horrors of contemporary animal life, far away and out of sight.

This book by Berry is one of the best books I have ever read, and it has shaped much of my writing and thinking, and not just about farmers.

Farmers, artists, filmmakers, machinists, mill workers, writers, union workers, craftsman small business owners, cafe operators and so many workers have seen their eyes upended by the new religion: money and more money, bigness and more bigness, by any means and at all costs.

It is by the measure of culture, rather than economics or technology,” wrote the very prescient Berry, “that we can begin to reckon the nature and the cost of the country-to-city migration that has left our farmlands in the hands of only five per cent of the people.”

A competent farmer is his own boss, lives freely and openly.

He has learned the discipline necessary to go ahead on his own, as required by economic obligation, loyalty to the land, pride in his work, and the meaning of family and community. His work requires intimate knowledge of the land and of animals, of weather and crops. He is utterly dependent on forces he cannot control – drought, storms, insects, floods, disease, sun and wind, government, politicians, regulators and economists, a fickle and unknowing public interested only in lots of cheap food, wherever it comes from, and however it is grown.

His workday requires instinct, long experience, practiced judgment, and hard labor. His days are not measured by other people or by any clock, but how he responds to necessity, interest, obligation, and debt. By the task and the obligation.

A farmer’s life depends on endurance and savvy, his farm lasts only as long as it is deemed necessary, or as long as he can work and stand up. He must master the intricate physical, emotional overlapping cycles of the earth – human and mechanical, animal and plant, controllable and uncontrollable – that is the life of the family farm.

The concentration of our farmlands into larger and larger holdings and fewer and fewer hands, writes Berry, brings us a consequent increase of overload, debt and dependence on machines.

A good farmer is a cultural product; not a technician or businessman. He is made by generations of experience and a great love of the land. When the farm dies, we lose land and the rich and meaningful culture of agricultural life. Rural America gave birth to the American experience, now it is mostly a wasteland, the place Main Street goes to die.

The farmer asks “what can I do with what i know?” The corporate farmer asks “how can I grow big enough to borrow money and make a profit?” We sometimes claim to be a Christian Nation, but are, instead a Corporate Nation, that is our common faith, and that is what doomed the family farm and the lives of so many other free men and women.

“It is within unity,” wrote Berry in “The Unsettling Of America,” that we see the hideousness and destructiveness of the fragmentary – the kind of mind, for example, that can introduce a production machine to increase “efficiency” without troubling about its effect on workers, on their product, and on consumers; that can accept and even applaud the “obsolescence” of the small farm and not hesitate over the possible political and cultural effects; that can recommend continuous tillage of huge monocultures, with massive use of chemicals and no animal manure or hummus, and worry not at all about the deterioration.”

I highly recommend this reading, it helps us understand the world we are living in today, and the challenge of empathy and communication.

For the careful and individual and iconic life of the farmer, we have substituted moral ignorance, the legacy of agricultural “progress.”

We are happy to trade the life of the individual for work that we hate for people who care nothing about us. At the core of the small farm I know of is freedom, individuality, love and humanity. That is what the corporation hates and fears the most.

Could Gus have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

Gus could have a thousand things, Joan, there is no end to the possibilities, or the money, or the strain, or the cost, but what we believe he has is megaesopahagus. And I’m not sure what this has to do with farming.

Great post Jon. Interesting that on the same day, I read your post and this one from Two Sparrows Farm – https://twosparrowsfarm.com/the-end-of-the-road/ . I am an animal rescuer, yet I fully support the true American farmer, and it’s often a struggle for me. Thank you for another in-depth perspective!