It was in the middle of my own Great Depression. \I had just moved to the country, was frightened and alone and overwhelmed, wondering over and again, “what have I done?” leaving my family and moving to a remote farm in a tiny village hundreds of miles from everyone and everything I ever knew.

I had never set foot on a farm before, let alone owned and lived on one with four barns, 36 sheep, two donkeys, some chickens, and cats.

A farmer came by to ask me what I was doing there, and I told him I was a writer. I told him I planned to grow stories, not crops. Good luck to you, he said, you ought to drive around and visit the farm widows and ask to see the Farm Journals the old farmers always kept.

So I did. I drove around and stopped at run-down old farms – not working farms any longer – and knocked on doors. When a farm wife answered, I told her I was a writer looking for Farm Journals.

I was astonished at the warm reception I received, the widows put some tea on and went off to closets and drawers and pulled up these tiny old leather-bound journals that their husbands and grandfathers used to keep track of expenses and purchases and life on their farms.

They refused to take any money for them; they were glad somebody was interested in the lives of their husbands.

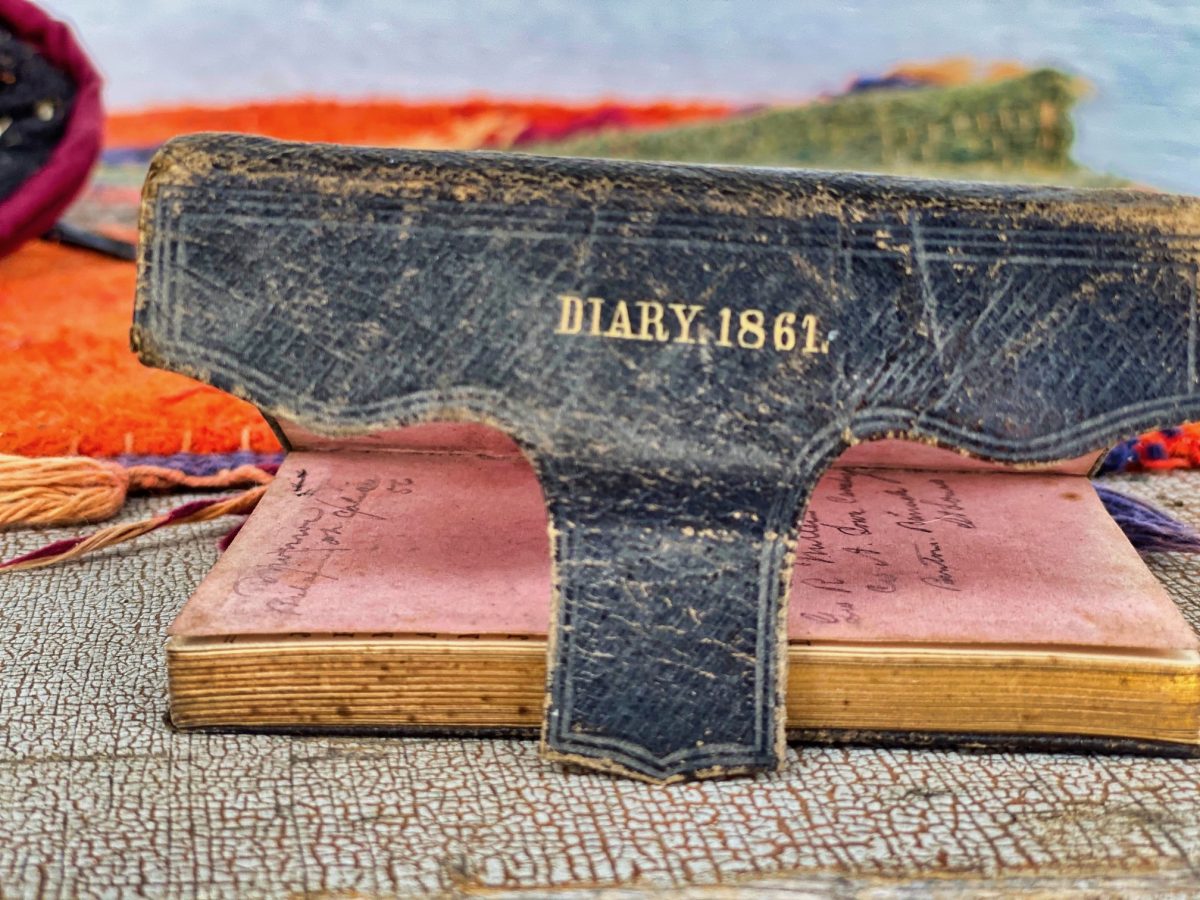

The first journal I got – the one above was from 1861.

The writing was spare and concise. “daughter Sarah died,” “Marye Colbe came to work,” “bull got out,” “bull back in,” “storm killed the cows,” along with lists of groceries and supplies purchased, money from milk and beef, carrots and wool, notes on the weather, and some terrified accounts of an eclipse the farmer thought signaled the end of the world.

The journals blew my mind. What a remarkable thing, a daily and faithful account of life on a farm before electricity, automobiles, social media, or telephones. Storms and weather were life and death things, not warnings on cable channels.

For all the hard work and hardship, these farmers wanted to tell their stories, wanted to keep a record of their lives as well as their debts and obligations.

The journals captured the urgency and drama of farm life, the mishaps, accidents, dead horses and cows; people killed falling off of horses, cuts that became infected and killed, awful storms that swallowed people and farms, failed or frozen crops, and colds and viruses that killed children quickly and often.

There was a lot of life and death in my journals. I drove to a score of farms and got 10 or 15 journals. They were mesmerizing to read.

I was humbled at the clarity, power and simplicity of the journal writing. They were authentic, faithful, informative, and poignant.

The farmers were good at math; their penmanship was strong and clear; they listed all of their debts and obligations. The widows were happy to give me these journals; they wanted them to be read and know, perhaps even published.

“They are of no use sitting up in a dresser,” these women told me, again and again. The journals were all turned over to the Washington County Historical Society at Maria’s suggestion when she met me and read them.

I kept just the one; I couldn’t bear to part with it. It lives right next to my computer.

These journals inspired the Bedlam Farm Journal.

I write on it just about every day. I try to faithfully record my life, good and bad.

I kept this one, from 1861, to remind me of those early writers, who faithfully recorded their lives in a small leather journal book. They humbled me; they had no choice but to use a few words and use them well.

I can’t turn on the computer without spewing a thousand words; they told the stories of their lives in a handful of sentences.

They inspired me to be honest and faithful, to write every day, and leave a full and honest account of my life. I am not a farmer, but one day somebody might find it interesting to go back through my Farm Journal, as I have done with theirs, and learn about a life way back in 2020.

No use my journal just sitting out there in space.

This blog post helps clear up an issue: I couldn’t draw an association between farming and blogs. But those farmers then felt what they were experiencing was significant enough to be recorded, as you do today. The main difference in recording is the technology.

But, how do you propose to archive your electronic works? With changing formats, media, and systems, would someone be able to read your material (100) years from now?

Electronic works are all archived, they don’t disappear..I don’t propose to do anything..

Roger’s dad was a fruit and dairy farmer in Western NY State. When he died. His collection of farm journals circulated through the family to see who wanted them. Roger asked for and received them. I have them – about 5-6 of them – since Roger died. Thank you for sharing the story of farm journals. I thought it was something only Roger’s dad did. Now I know the fascinating history behind this.